"Human cells are continuously replaced, and much of the body is rebuilt over time. By the age of 65, you will have gone through six skeletons, four sets of muscles and guts, and your red blood cells will have been renewed almost 200 times. So can you be regarded as the same person you were 20 years ago?"

—Mark Stephens, The Philosophy Notebook

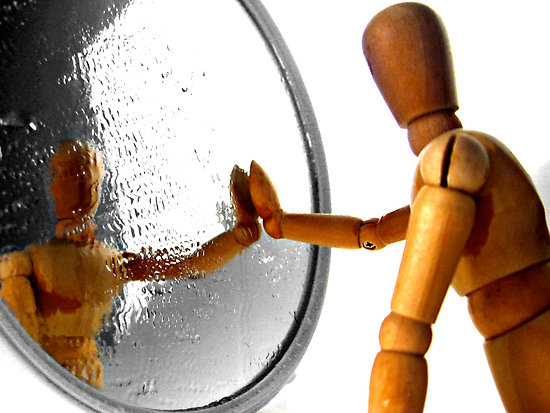

The concept of self-identity is problematic indeed. What do we mean when we refer to ourselves as "I"?

Imagine that you're at your friends house, chilling on the couch while they're fixing bacon cheddar burgers (your favorite) in the kitchen. All of a sudden you hear your friend yelp in pain:

"Shit!"

"What happened? Are you okay?"

"Yeah, I just nicked my hand."

I nicked my hand? Usually, claims to possession are to external objects, so who is this I that the hand belongs to? You could ask your friend: are you not your own body? If your friend responds that they are their body, then they are, as noted by Stephens, essentially an entirely different person than they were 5 years ago, 10 years ago, 15 years ago, and at every single point in between. If we are our bodies, then we can never definitively state who "I" is, for "I" is constantly in flux. The philosopher Rebecca Goldstein captures this problem in Betraying Spinoza:

"I stare at the picture of a small child at a summer's picnic, clutching her big sister's hand with one tiny hand while in the other she has a precarious hold on a big slice of watermelon that she appears to be struggling to have intersect with the small o of her mouth. That child is me. But why is she me? I have no memory at all of that summer's day, no privileged knowledge of whether that child succeeded in getting the watermelon into her mouth. Its true that a smooth series of contiguous physical events can be traced from her body to mine, so that we would want to say that her body is mine; and perhaps bodily persistence is all that our personality consists in. But bodily persistence over time, too, presents philosophical dilemmas. The series of contiguous physical events has rendered the child's body so different from the one I glance down on at this moment; the very atoms that composed her body no longer compose mine. And if our bodies are dissimilar, our points of view are even more so."

Given that we are all dualists by birth (mind/body separation), your friend might not understand your criticism. We are inclined to believe that "I" is somewhere behind the eyes, experiencing the world using the vehicle that is the rest of the body. This is no surprise as most of your brain is dedicated to the eyes just like the other primates, so they are of utmost importance. But if something lies beyond them, what is it? We may believe that there is something inside that makes us, but can we pinpoint it? Some practices of Buddhism teach that we can't. There is no I, for the concept of self is an illusion. Nevertheless, we shall try.

The first, and oldest, argument for self-identity is the concept of the soul or the spirit. In this case, the real you is an essence that is separate from the body, yet inhabits it. It will also continue to exist after the body dies. This concept, as philosophical arguments over the last few hundred years have shown, raises many more questions than it answers. Where does the soul come from? Where does it go after death? Do old souls inhabit new bodies or are souls constantly generated? How do you know? How could you know? Question such as these predate the field of Neuroscience, which has opened up an entirely new set of questions. As Sam Harris noted in The Moral Landscape, we now know that the ability to remember, to move, to love, to think, etc. require a brain. In just damaging the brain in specific ways, we can remove all of these abilities, so how could a human exhibit these abilities without one?

Memories

We can reasonably claim that we are our minds or, more specifically, our memories. We go to great lengths to preserve them (even paying to be reminded!), they influence our actions, and sustain our beliefs. If we are but our memories, then we are justified in our scrupulous care for them. Unfortunately, this idea also comes with its problems.

If the self is the memory it contains, then we are even more fragile than we thought we were. I can imagine an instance in which I take a vicious blow to the head, resulting in a permanent retrograde amnesia. I can no longer recall the events of the last 15 years. Am I still the same person? Given that memories have such an influence on behavior, would I still exhibit the same qualities as the Charles before the incident? Might my character change? I find it reasonable to assume that the difference would be immediately recognizable to those closest to me.

Head trauma might not be something we all foresee in our futures, but what about an affliction much, much more likely?

I once read a story about an elderly woman, hosting a dinner for her family. In the middle of eating, she stands up, grabs a broom, and begins swinging it wildly. She exclaims that there are witches flying around the kitchen trying to get her. You may assume that she is hallucinating. Surely there isn't anything out to get her, but her family members immediately noticed what happened. Their grandmother had moderate to advanced Alzheimer's disease, and her current reality melded with the memory of a movie she had watched: The Wizard of Oz.

Who is this person inhabiting their grandmother's body? Is she part Nana and part Dorothy? If we are our memories, then Dementia had already killed the person they loved. This would make these brain diseases worse than any other we can imagine, for it leads to a stranger masquerading as oneself.

To be fair, our memory is pretty bad without any intrusion. Many of us experience infantile amnesia: we have a hard time remembering our childhoods. If I could travel back in time 15 years, the Charles I would be observing would almost be as much a stranger to me as he would be to anyone else. I couldn't really tell you anything of worth about him. I could give you general bits of information, such as that he went to church, was desperate to be liked, and probably pondered what his life would be like when he's me, 15 years older; however, we would hardly be one and the same. I only have to visit one of my old Facebook or MySpace pages to see that. It would be difficult to make memories the sole identifier of self when we can't remember who we were, or why we were, at an earlier date, as Goldstein noted when looking at an old photograph.

If our current bases for self-identity can be altered by the renewal of skin cells, a quick jab, or the destructive potential of brain disease, then what can we consider I to be? Was Captain Lucard committing suicide every time he beamed up in Star Trek? The forerunner for self-identity could be consciousness, as its absence is the reason we consider incidences in which we end up in a vegetative state, in our wills. Yet consciousness is almost as tricky to investigate as the soul. Right now, we really don't have an answer but the Buddha may have had the closest we have to one.

Until next time!

—Mark Stephens, The Philosophy Notebook

The concept of self-identity is problematic indeed. What do we mean when we refer to ourselves as "I"?

Understanding the Problem

Imagine that you're at your friends house, chilling on the couch while they're fixing bacon cheddar burgers (your favorite) in the kitchen. All of a sudden you hear your friend yelp in pain:

"Shit!"

"What happened? Are you okay?"

"Yeah, I just nicked my hand."

I nicked my hand? Usually, claims to possession are to external objects, so who is this I that the hand belongs to? You could ask your friend: are you not your own body? If your friend responds that they are their body, then they are, as noted by Stephens, essentially an entirely different person than they were 5 years ago, 10 years ago, 15 years ago, and at every single point in between. If we are our bodies, then we can never definitively state who "I" is, for "I" is constantly in flux. The philosopher Rebecca Goldstein captures this problem in Betraying Spinoza:

"I stare at the picture of a small child at a summer's picnic, clutching her big sister's hand with one tiny hand while in the other she has a precarious hold on a big slice of watermelon that she appears to be struggling to have intersect with the small o of her mouth. That child is me. But why is she me? I have no memory at all of that summer's day, no privileged knowledge of whether that child succeeded in getting the watermelon into her mouth. Its true that a smooth series of contiguous physical events can be traced from her body to mine, so that we would want to say that her body is mine; and perhaps bodily persistence is all that our personality consists in. But bodily persistence over time, too, presents philosophical dilemmas. The series of contiguous physical events has rendered the child's body so different from the one I glance down on at this moment; the very atoms that composed her body no longer compose mine. And if our bodies are dissimilar, our points of view are even more so."

Given that we are all dualists by birth (mind/body separation), your friend might not understand your criticism. We are inclined to believe that "I" is somewhere behind the eyes, experiencing the world using the vehicle that is the rest of the body. This is no surprise as most of your brain is dedicated to the eyes just like the other primates, so they are of utmost importance. But if something lies beyond them, what is it? We may believe that there is something inside that makes us, but can we pinpoint it? Some practices of Buddhism teach that we can't. There is no I, for the concept of self is an illusion. Nevertheless, we shall try.

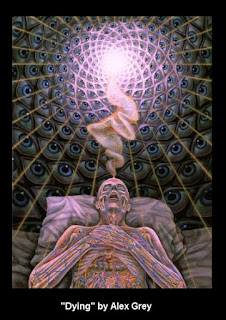

What's there besides the body?

The SoulThe first, and oldest, argument for self-identity is the concept of the soul or the spirit. In this case, the real you is an essence that is separate from the body, yet inhabits it. It will also continue to exist after the body dies. This concept, as philosophical arguments over the last few hundred years have shown, raises many more questions than it answers. Where does the soul come from? Where does it go after death? Do old souls inhabit new bodies or are souls constantly generated? How do you know? How could you know? Question such as these predate the field of Neuroscience, which has opened up an entirely new set of questions. As Sam Harris noted in The Moral Landscape, we now know that the ability to remember, to move, to love, to think, etc. require a brain. In just damaging the brain in specific ways, we can remove all of these abilities, so how could a human exhibit these abilities without one?

Memories

We can reasonably claim that we are our minds or, more specifically, our memories. We go to great lengths to preserve them (even paying to be reminded!), they influence our actions, and sustain our beliefs. If we are but our memories, then we are justified in our scrupulous care for them. Unfortunately, this idea also comes with its problems.

If the self is the memory it contains, then we are even more fragile than we thought we were. I can imagine an instance in which I take a vicious blow to the head, resulting in a permanent retrograde amnesia. I can no longer recall the events of the last 15 years. Am I still the same person? Given that memories have such an influence on behavior, would I still exhibit the same qualities as the Charles before the incident? Might my character change? I find it reasonable to assume that the difference would be immediately recognizable to those closest to me.

Head trauma might not be something we all foresee in our futures, but what about an affliction much, much more likely?

What is to be said of Dementia, which affected 46 million people in 2015? Or Alzheimer's disease in which 70% of the risk is believed to be genetic?

I once read a story about an elderly woman, hosting a dinner for her family. In the middle of eating, she stands up, grabs a broom, and begins swinging it wildly. She exclaims that there are witches flying around the kitchen trying to get her. You may assume that she is hallucinating. Surely there isn't anything out to get her, but her family members immediately noticed what happened. Their grandmother had moderate to advanced Alzheimer's disease, and her current reality melded with the memory of a movie she had watched: The Wizard of Oz.

Who is this person inhabiting their grandmother's body? Is she part Nana and part Dorothy? If we are our memories, then Dementia had already killed the person they loved. This would make these brain diseases worse than any other we can imagine, for it leads to a stranger masquerading as oneself.

To be fair, our memory is pretty bad without any intrusion. Many of us experience infantile amnesia: we have a hard time remembering our childhoods. If I could travel back in time 15 years, the Charles I would be observing would almost be as much a stranger to me as he would be to anyone else. I couldn't really tell you anything of worth about him. I could give you general bits of information, such as that he went to church, was desperate to be liked, and probably pondered what his life would be like when he's me, 15 years older; however, we would hardly be one and the same. I only have to visit one of my old Facebook or MySpace pages to see that. It would be difficult to make memories the sole identifier of self when we can't remember who we were, or why we were, at an earlier date, as Goldstein noted when looking at an old photograph.

What the hell is "I"?

If our current bases for self-identity can be altered by the renewal of skin cells, a quick jab, or the destructive potential of brain disease, then what can we consider I to be? Was Captain Lucard committing suicide every time he beamed up in Star Trek? The forerunner for self-identity could be consciousness, as its absence is the reason we consider incidences in which we end up in a vegetative state, in our wills. Yet consciousness is almost as tricky to investigate as the soul. Right now, we really don't have an answer but the Buddha may have had the closest we have to one.

Until next time!

Comments

Post a Comment